Holding on to Who We Are

I am not exactly sure what got me started, but I’ve been working my way through a self-assigned reading list on antisemitism. I started with Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition by David Nirenberg (a bit dense for extracurricular reading). Next up was People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present by Dara Horn (wonderfully written and thought provoking). And now I’m onto the newest publication, Antisemitism, an American Tradition by Pamela Nadell, a history professor at AU.

I am still wrapping my mind around the takeaways, but thus far I’ve been struck by a chapter from Horn’s work. She points out the story we all hear about Ellis Island registrars intentionally or inadvertently adjusting the names of Jewish immigrants as they made their way through a harried intake process is, in fact, a Jewish myth.

The truth, Horn explains, is that Jewish immigrants made deliberate choices to Americanize their own names soon after their arrival to avoid discrimination and improve their job prospects—an urgent consideration in turn-of-the-century America. Jewish immigrants needed to make a new life for themselves and their families, and they knew the better they were at publicly masking their Judaism, the easier it would be.

Thus began a delicate American Jewish tradition of maintaining our Jewish identities while doing what we could to fit in. Up until now, I thought this dance was a thing of the past. Obscuring names and associations and forgoing outward expressions of Jewish faith seemed to me like the stuff of history books. After all, I’ve grown up during an era of American Jewish flourishing. That we might be back here, putting a baseball cap over our kippahs or quietly removing Jewish indicators on our LinkedIn has caught me by surprise.

In 2023, Hillel found that 1 in 3 Jewish college students hid their identity after October 7. And last week, the Washington Post published results from a September poll that found in the past year, 42% of Jewish Americans avoided publicly wearing, carrying, or displaying anything that might help people identify them as Jewish. Discouragingly, younger Jews were more likely to say they avoided displaying Jewish symbols—53% of those under age 35—than older groups.

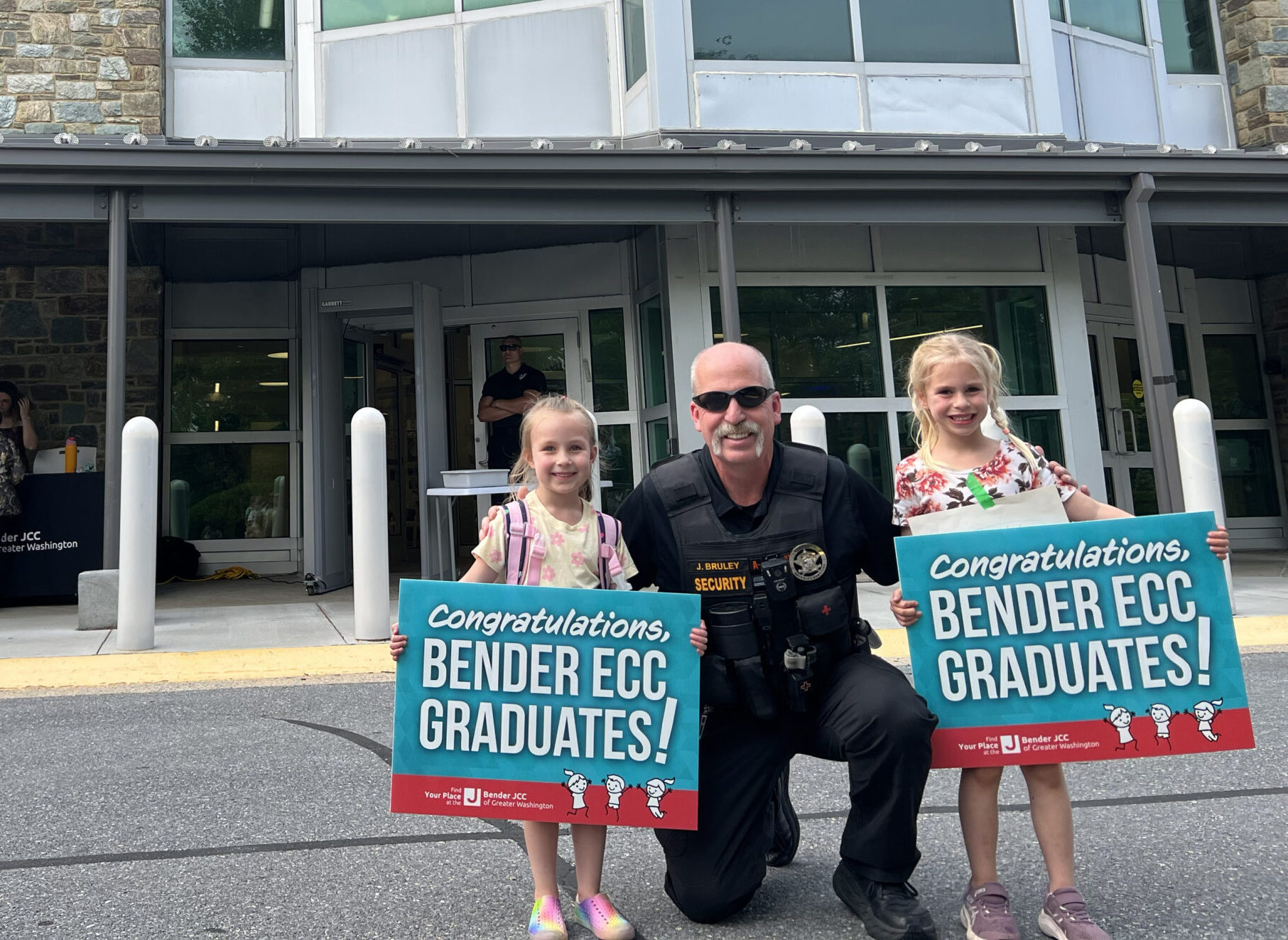

After my deep dive into antisemitism’s history, I have a much greater understanding of how deeply embedded antisemitism is in our societies, and therefore how hard it can be for a community to try and fit in and fight antisemitism simultaneously. Embracing and relishing our Jewish identity and being sober minded about the state of antisemitism in America, and indeed the world, all feel like nonnegotiables.

That’s why I’m resolved that we must not cede either goal. We can double down on our work to strengthen our Jewish identities even as we make real-world adjustments to account for our safety. Hate may force us to make compromises or short-term sacrifices, but it must not define who we are or diminish our commitment to Jewish life. We owe it to generations past and future to continue fighting antisemitism and the hatred that would see us limit our Jewish expression. The current growth in hate cannot continue. Confronting it must be a central priority for our Jewish community.